Climbing to New Heights on Mount Rainier

For Pix, click here: http://picasaweb.google.com/fritzwiese/2007MtRainierClimbOdyssey

“It was the best of times; it was the worst of times.” Climbing to the summit of the 14,410 foot Mt. Rainier, known as the most physically demanding mountain ascent in the lower 48 states, was an exhausting, thrilling, at-times-scary, unforgettable odyssey. For a sabbatical entitled, “Climbing New Heights,” this event was designed as the pinnacle, in terms of the sabbatical’s physical dimension. A few years back, Tom Eldridge offered a popular book for Christian men entitled Wild at Heart. Eldridge argued that men’s lives are fully engaged by entering three spheres: a battle to fight, a woman to love, and an adventure to live. Rainier, our nation’s 3rd highest mountain (behind McKinley in Alaska and Whitney in California) certainly fell into the “adventure to live” category.

After a heart-opening series of days learning with the ministry of Mars Hill Church in Seattle, I picked up my college buddy, Andy Kipker, from the airport on Saturday, Aug 4 and drove to Whittaker’s Bunkhouse in Ashford, WA, which would serve as base-camp for the summit attempt. The next day, we did “school” with our professional guides at RMI (Rainier Mountaineering International), learning how to use an ice ax, crampons, rope systems, and self-arrest techniques in case you found yourself sliding down a 45 degree 1,000+ foot slope of ice, careening toward a gaping crevasse. That night, after stocking a backpack that would have tripped airport weight regulations, we spent a second night “resting,” since a few nerves prevented any sweet dreams or true sleep. Monday morning, our team, minus one who found the school too taxing, drove the 50 minute ride to Paradise inside the park. There, around 9 AM, day one of the climb began at the 5,500 foot base of the mountain; the paved path soon transitioned to snow field, and at 3.45, we had reached camp #2, Camp Muir at 10,000 feet. Muir provided an awesome vista. While clouds had rolled in at 5,000 feet, blanketing the northeast with cotton balls, our vantage was clear. Rising defiantly of the cotton clouds, Mt St. Helens, Mt. Hood and Mt. Adams all gleamed in the sun’s rays. Although compared to space, Rainier is nothing but a mole hill, we felt we were standing on top of the world—but we weren’t at the top yet.

The strategy was to eat our freeze dried dinners and then “rest” as best we could in the simple wooden shack that reminded me of the concentration camp bunkhouses I visited in Germany at the beginning of the summer. Earplugs helped a little bit with the rustling of others’ sleeping bags, but didn’t do much for the questions swirling inside each of our heads. “What would the weather be like? Were we up to the challenge? Did we pack everything we need? What if something happened?” After about 70 minutes of genuine sleep (for which I was grateful), I snuck outside to use the bathroom, and was rewarded with one of the journey’s profound pleasures: stars brilliant beyond belief. A miraculous Milky Way. That view and a renewed realization that “this is my Father’s world,” reminded me what a gift this opportunity was.

At 11 PM, our guide awoke us. It was time to eat and start. Of all those who attempt summiting Rainier, only 60% make it. Beyond physical and mental issues, one challenge is weather. This morning, we had been blessed with mild and clear air. So after hydrating and my billionth bagel, we roped up, secured crampons, illuminated our head-lamps, strapped on a pack that felt like both my children were hiding inside, and ventured off, minus a second of our mates, who had decided the climb “didn’t feel right.” It’s an eerie feeling climbing in the dark. Earlier in the summer, I had experienced the sensation at 4 AM on the start to Long’s Peak. Alone. No ambient light from starts or moon under the thick forest canopy. I had jumped pretty high when a small animal shattered the silence just off the path. At least here on Rainier, other lights shone than only my own. The disturbing difference soon emerged. Ten minutes into the climb, I noticed teammates ahead slowing off the pace for just a moment. When I arrived at the spot, the reason was clear: a two foot wide gaping crevasse. Jagged twisting walls were visible in the narrow beams of one’s head lamp, but not the bottom of the crevasse. That was left for your imagination. In a sense, I realized that was the most profound crossroad of the trip. Either you were going to trust in the security of your roped teammates and take the leap of faith, or you weren’t. That first two foot step (which felt like 10) wasn’t the widest of the trip, and it wasn’t the most narrow, but it felt great to feel the solid ice under my foot on the other side!

All in all, we were to traverse over 100 crevasses. 100 other “leaps of faith,” sometimes while hiking backwards, or up incredible angles. However, I don’t think you could count the number of steps as we pushed on to the 14,410 foot summit. We appreciated our guides steering us clear of Disappointment Clever, unpassable because of the late-summer crevasse chaos, but it meant that after ascending to that juncture, we had to DESCEND an extra 700 feet, hike a while, and then re-ascend the altitude. I think from Camp Muir, the trip to the summit is only 5 miles. But the mile UP, with each step in snow and ice, along with the extra ups and downs, plus the unrelenting pace of the guides who wanted to get us up and down before the weather turned, made it the physical challenge of my life. The last 60 minutes of my second Columbus Marathon were probably the most grueling single hour of my life; but in terms of a holistic experience, this summit climb, with the never-ending descent as kicking-butt compliment was the hardest.

Anyway, in terms of making a long account even longer, we celebrated the summit at 7.35 AM on Tuesday morning, August 7. We were so exhausted that not one of us took the guides up on the opportunity to walk across to the other side of the summit (which is a snowy volcano cauldron depression). I need to trace down the facts, but I think there is 66% less oxygen on the mountain than the oxygen rich atmosphere of Dayton, so we breathed. After 15 minutes of rest, a few photos, and forcing yourself to eat, the teams prepared for descent. By 1 PM, we had returned to Camp Muir. We quickly refilled water bottles, packed our sleeping backs, tended to blisters, and continued with the journey down to Paradise, where we arrived after a rainy, cloud covered progression at 5.30 PM.

Was it worth “climbing new heights” to the top of Mt Rainier? Absolutely! Would I do it again? No way, (unless a new house was involved, or a church capital campaign could be bypassed). This 40 year old had an itch, and Mt Rainier (along with Long’s Peak and some Switzerland Alps hikes) scratched it good. J Seeing God re-color the world with sunrise from the near summit of one of the country’s tallest peaks was uniquely spectacular and motivating. Committing all your God-given physical and mental energy toward a team effort that at moments seemed insecure, and then succeeding, was exhilarating and confidence-strengthening. Pushing the envelope on the side of such a inhospitable incline reminds you to treasure your abundant God-given comforts.

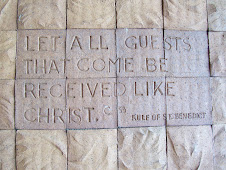

Moses certainly had his mountain moments. I’m no Moses. Maybe God thinks of climbs like this along the lines of the Babylonians trying to climb to the heavens with their ill-fated tower. But I’d like to hope that in the spirit of Moses, Noah, Jesus, and the Pentecost disciples, God gave me this mountain moment to clarify my relationship with Him and teach me a few things. Here are a few nuggets of faith insights from Mt Rainier that I’ll be praying about. Perhaps they’ll expand into a sermon one day:

· Christians need to rope up together. If somebody slips, we’ve got to make sure we catch each other. We’re all able to live more boldly, if we know others have our backs (or belts).

· You’re silly if you think you can make it up the mountain without a guide. Life-sucking crevasses loom hidden under the snow. You better be following someone who knows the lay of the land. Christians call this guide Jesus.

· On the mountain, there’s 66% less oxygen than at sea level. Mountain guides teach you how to breathe correctly; if you don’t work on breathing techniques, you’re in trouble. For Christians, we count on the resurrected Jesus breathing on us, as he did the first disciples. That changes everything. We need to pay attention to the Holy Spirit, our guide instructing us how to breathe the fresh air of new life.

· On the climb, you must eat and drink. Because of the altitude and exhaustion, sometimes you don’t feel like it. But it’s essential. As Christians, we rely on Jesus’ weekly feeding of us in worship, centered in the bread and wine of Eucharist. Sometimes, in our laziness, or because life has left us too tired, we don’t feel like getting to the Lord’s table on the weekends, but it makes all the difference.

· New vistas, insights, and confidence aren’t achieved without risks and sacrifice. The climb of faith includes at times heavy burdens (backpacks), scary leaps of faith (crevasses), periods of darkness when only the next few steps are visible, resting points that are so steep you’re water bottle will slide out of reach if you’re not careful, and slippery steep slopes that make every muscle in your leg burn. But we claim Jesus’ promise that he is our faithful guide “with us always, even to the end of the age” (or the end of the hike). With Jesus, out of the darkness, there comes a great light, and joy comes in the morning. Through the journey, we grow in fear and love of the One who made the mountain, who guides our steps on the mountain, and teaches us on the mountain. By following him as part of a team, we gain insight, confidence and ability to climb again and lead others on the journey.

· I pray that as Jesus’ disciples gained new insight by witnessing his Transfiguration on the mountain, so too, the Holy Spirit will sear into my spirit the lessons of this incredibly difficult, but exhilarating and insightful mountaintop experience of “climbing new heights.”

Monday, August 13, 2007

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment